Folktales and Oral Tradition in Africa

The primary form of expression and communication of the history and experiences of African peoples is through Oral Tradition. For most of its history, sub-Saharan Africa has existed with pre-literate societies. There are no written creeds, sacred scriptures, or recordings of social customs and practices from traditional societies in sub-Saharan Africa. Religion and culture are “written not on paper but in people’s hearts, minds, oral history, rituals, and religious personages” (Mbiti, 1969:4). As a result Oral Tradition is the key element for preserving and communicating religious and social ideals and experiences to future generations. Within African traditional philosophy, those who are yet to be born are potential members of the African community. Historically, folktales were the main form of passing down moral values and social traditions to future generations.

The Science of Folklore

Folklore has been the subject of scientific study and analysis since the inception of Anthropology. Early Anthropologists often took a negative view towards folklore. For example, Powell writes that “the science of folklore may be defined as the science of superstitions, or the science of vestigial opinions no longer held as valid” (Powell, pg. 1). Until recently, professional historians have generally equated folklore with “rumor, hearsay, untruth, and distortion, and have rejected out of hand the spoken tradition for the written word” (Dorson, pg. 1). Current scholarship however has recognized folklore and oral traditions as key tools for ethnographic research and for studies in history, religion, linguistics, and many other disciplines (Burns, pg. 109). Folklore is immensely valuable in ethnographic research because it “functions within a social cultural context whose cultural content and social integration it both reflects and determines” (Fernandez, pg. 3). For these reasons, I have decided to study folktales from Alego Central as a means for understanding the socio-cultural history of Luo peoples in that region.

Background on Alego

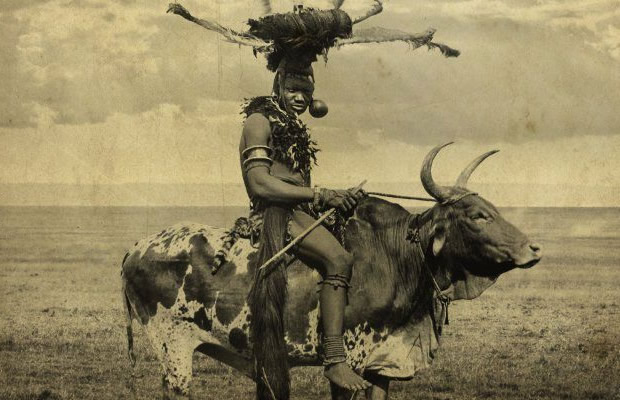

The Luo are a Nilotic people inhabiting the region around Lake Victoria and stretching from Western Kenya to Northern Uganda, Southern Sudan and Ethiopia, Eastern Congo, and parts of Tanzania. Their language is Dholuo and their main forms of livelihood are now fishing, farming, and raising cattle. The Luo probably originated in Southern Sudan around 3,000 B.C. and migrated to Kenya and Uganda around 1500 A.D. (Ogot, 1967). The Luo currently are one of the largest tribes in Kenya with an estimated population of 4 million. They represent a diverse group with a long history of migration and include 25 subgroups occupying distinct territories or pinys within Kenya. The Jo-Alego represent one of the 25 piny and were established as a distinct administrative unit by the end of the 19th Century (Cohen, pg. 31). The Jo-Alego historically settled in the area now known as Siaya within Nyanza Province. This paper focuses on the area of Alego Central within Siaya District.

Folktales in Alego Central

Traditionally in Alego Central, folktales were told to children at night by their mothers or their grandmothers in the village. The children would sit around the fire as the women cooked. According to the women that I interviewed, folktales were a way of keeping the “children awake so that they would not sleep before they could eat.” The folktales were used for “teaching morals and also to entertain the children.” There are certain names and symbols that commonly appear in Luo folktales. Obong’o, for example, is a common name that appears in much of Luo folklore. Luo folktales generally include a longer narrative with symbolic characters and actions and a short song which summarizes the main elements of the story. While the longer narrative may vary slightly from each story-teller, the essence of the folktale is captured in the song which is easily remembered and passed on from generation to generation.

Emic Presentations of Luo Folktales

For this paper, I listened to and recorded one Luo folktale from Alego Central that reflects Luo beliefs and customs regarding marriage. The folktale was translated into English and is presented here in its English version with the main chorus in both English and Luo. Based on an analysis conducted within one family, the folktale has been passed down for at least four generations. The folktale is still taught in many parts of Allego Central, and the narrator of the story suggested that it must have originated hundreds of years ago because they included some “deep Luo words which are no longer understood by the younger generations.”

Baer ok pand: Beauty cannot be Hidden – The Story of Agola

“Agola was a very beautiful girl. Many of her peers hated her because of her beauty. Most young men wanted to marry her, but the tradition held that in every season there would only be certain a group of young women and young men who would be qualified to be married. So, this group would go out into the fields and display their talents and the young men would come and pick whoever pleased them most. As usual, the girls would leave their homes together, travel from a common place and walk to the fields together. So, while they were on their way to the fields one year, the other girls conspired against Agola and they said ‘She is too beautiful. When we go to the fields, none of the men will want to pick us. So, we had better turn her into an mbero (cooking stool).’

So the other girls turned Agola into a cooking stool and then they carried it along with them to the fields. On their way, they met an old man who said to them, ‘girls you are so beautiful but if that cooking stool was a woman, I bet it would be more beautiful than you.’ At hearing this, the girls were furious and they decided they would now turn Agola into a grinding stone. So they turned her into a grinding stone and carried it with them as they walked. On their way, they met another old man who said to them ‘Girls you are so beautiful, but if the grinding stone was a woman, I bet it would be more beautiful than you.’ So the girls were furious again and they decided that they would now turn Agola into a gourd. And so they did. Then along the way, they met an old woman, who like the others thought that the girls were so beautiful, but if the gourd that they were holding was a woman, it would be more beautiful than all of them. The girls were so furious and then they decided, ‘We have no choice, we have to turn her into a dog, with one bad eye.’ And so they did. And all along to the fields, no one commented about the dog. The girls finally reached the field and all of them found suitors, and of course Agola did not find a suitor because she was a dog with one bad eye.

It turned out, however, that the most handsome warrior, Obong’o, had not been in the field at the time to select any woman. He had been about his business and was not in any hurry. His mother was getting furious with him because he was missing the season for finding a wife. If Obong’o didn’t hurry he would be stuck with a lazy wife or an ugly woman with bad character, because those were the always the ones who remained in the fields after the others had been taken. So at his mother’s nagging, Obong’o set off to the fields to find a wife. When he reached the field, however, he was shocked because this time not even the ugly ones were left. All he saw in the field was a dog with one bad eye. Obong’o wanted to leave, but something made him go back to the field. He had pity on the dog and took it home with him. When he got home, his mother was not very impressed. She scolded him about missing his chance for finding a wife. Now Obong’o would never get married because his season had passed. So, Obong’o and his mother turned in for the day and early the next morning as was their custom, they set out to the shamba to do their normal ploughing. They left the dog with one eye behind, and no one else was in their homestead, or so they thought.

While Obong’o and his mother were away, the charms that the girls had used on Agola began to wear out. Now the dog skin that was covering Agola could be removed. So Agola removed the dog skin when no one else was around. Because of her gratitude for being rescued from the fields, Agola decided to clean the house and cook for Obong’o and his mother before them came back from the farm. And while Agola worked, she would sing this song:

Lele Agola. Lele Agola. Lele Agola. Jaber lou.

Oh Agola. Oh Agola the most beautiful above the rest. (x2)

Lo ki kidi, wei no no.

They turned you into a stone and it was like nothing (it didn’t matter).

Lo ki aguata, wei no no.

They turned you into a gourd and it was like nothing.

Lo ki mbero, wei no no.

They turned you into a cooking stool and it was like nothing.

Lo ki guok ma wang’e dhiek.

Then finally they turned you into a dog with a bad eye.

And after she finished her work, Agola covered herself again with the dog skin so that she would not be discovered.

The first day when Obong’os family came home, they were surprised to find the house clean and the food prepared. The work had been done so well, but when they asked the neighbors no one knew who had done the work. So every day, Agola continued to clean and cook, and every day when she finished she covered herself again with the dog skin. And each time, Obong’o came home in amazement to find what Agola had done.

Then one day, when Obong’o and his mother couldn’t figure out who was doing the housework, they decided to set a trap. Obong’o pretended that he had left for the ploughing, but instead stayed behind and hid at the neighbor’s homestead to watch if anyone came to do the work. So Obong’o stayed behind and watched for quite a while, but nothing was happening. When he was about to give up, Obong’o noticed that his often quiet dog was moving about the compound as if looking for someone. And then he watched as the dog removed its skin. To his amazement, Obong’o saw the most beautiful woman, coming out from underneath the dog skin. He watched her go about her work and listened as she sang her song. And he remembered stories he had heard about the beautiful Agola. Everyone in the village had thought that Agola had been lost and disappeared. But all along Agola was right there in Obong’o’s homestead.

Obong’o didn’t want to scare Agola, so he went and crept up and stole away the dog skin. Then he ran back to their farm to gather the family and their neighbors. He tried to explain what he had seen, but they could not believe him. So Obong’o showed them the dog skin. And they decided to rush back to the homestead to see if Obong’o’s story was true. Since Agola was not expecting anyone to be back until later in the day, she was caught unaware. Suddenly the crowds of people entered the homestead with awe and ululations, Agola was shocked and wanted to hide again in her skin and retreat back to her quiet dog life, away from everyone who had hated her. But Obong’o would not give the skin back to her. He had fallen in love with her the minute he saw her and had made up his mind that she would be his wife. Of course Obong’o’s mother could not believe her son’s fortune that he ended up with the most beautiful girl in the village.”

An Emic Interpretation of the Story of Agola

According to the narrator of this folktale, the story is about beauty, jealousy and traditional Luo marriage. All of the young girls did not want Agola to be seen because her beauty surpassed their own. However, no matter how much they tried to cover it, Agola’s beauty continued to shine through. She was beautiful not only on the outside, but also on the inside. The folktale therefore teaches children about true beauty and that cursing others often produces blessings instead. The narrator also revealed that in traditional village life, the youth were divided into age sets. After passing through circumcision and reaching a certain age, it was expected that everyone in the age set would get married. The practice of going to the fields each year and searching for a wife was the main form of courtship and marriage in traditional Alego Central.

Etic Interpretation and Analysis

The story of Agola reveals a great deal about traditional Luo culture in Alego Central. The folktale is not intended as a historical narrative, but nonetheless describes much about the history, morality, and social customs of the area. Below are some of the major cultural elements that I’ve identified in the folktale with ethnographic descriptions based on an etic interpretation of the narrative as well as additional library research and participant observation of traditional bride price negotiations and weddings.

Age-sets

The folktale presents very clearly the concept of age-sets within both male and female populations. In traditional Luo society, children and youth were divided into age-sets based on their year of birth. Unlike other tribes in Kenya, the Luos did not practice circumcision, but at the age of puberty, males went through a rite of passage where their lower front incisors were removed. This initiation ritual signified the transition to adult status and enabled him to marry within the society. For females, there were also several rites of passage. Girls used to live with their grandmothers and after their first menses they would participate in initiation rites. According to an interview with Sophia Amina, there were two main initiation rites done on females. One was to remove the six lower teeth, as done with the males. Another was to practice cicatrization, or making marks across the belly with a sharp knife. After the marks had been made, the girl’s waist was covered with a string of coloured beads. These were signs that she was now ready for marriage. The practice of removing incisors from females ceased earlier, while the rite of passage continues for males in some areas to this day. In the story of Agola, the males and females who go to the field represent a single age-set that has completed the rite of passage to adulthood and whose members are now eligible for marriage.

Roles of Elders

In the story of Agola, the girls who are on their way to field to find a husband encounter three elders, two males and one female. Each of the elders examines the beauty of the girls and then comments. In traditional Luo society, marriage was arranged by elder matchmakers in the community. According to Cohen and Odhiambo, a young man wishing to marry would ask a Jogam or intermediary to identify a wife for him and to lead the negotiation process (pg. 109). The Jogam was normally an uncle or elder male in the community. In addition, the Pim (or old woman) played a vital role in teaching girls about marriage and sexuality and in ushering them into married life (Cohen, pg. 93). The girls on their journey to the field seem to have encountered two Jogams and one Pim, all of whom recognized the superior beauty hidden within Agola.

The Marriage Process

I have had the privilege of observing and participating in two sessions with a team of Jogam in Nairobi as well as in Siaya. The Jogam represent the male suitor to the father and uncles of the intended wife. The Jogam are to conduct at least two official visits to express the young man’s intention and also to negotiate the bride price. Typically, the Jogam will make inquiries and then visit the homestead of the young woman, being welcomed by her family with a large meal. It is a requirement for the Jogam to eat chicken in the home of the girl in order for the visit to be considered official. The eldest member of the Jogam serves as the spokesman for the young man, while the elder brother of the girl’s father speaks on behalf of her family. During the first visit, stories and parables are told to introduce the young man and present his request for marriage. These stories are normally told in the forms of parables. For example, one elder described the reason for his visit as “there is a certain young man who saw a flower growing in your homestead and has been captivated by its beauty.” After introducing the suitor, the Jogam then negotiate the bride price, which in Alego is to be paid in male-female pairs of cattle and goats.

During the second visit, the animals are delivered to the homestead of the bride’s family and the ropes used to tie the animals are kept as evidence that the bride price has been paid. A riso ceremony is then held in which the bridegroom must identify the bride from among her sisters, all veiled and dressed in like manner. Upon successful identification, the bride and groom are then united and their families also joined together with songs and celebration. Afterwards the bride and groom leave the homestead in order to consummate the marriage. The major details of this traditional wedding ceremony are evident in the folktale of Agola. Obong’o is able to identify Agola even when she is wearing the dogskin. Then family and neighbors all enter the homestead with ululations and celebrate the new marriage.

Interestingly, the folktale presents the main method of acquiring a mate as finding one’s bride in the field and carrying her off to his homestead. Kidnapping brides was a common form of marriage in Alego Central until recently. When this happened, the process of negotiation would occur in secret or after the bride had already been kidnapped. One of the families that I interviewed explained that many girls were kidnapped while fetching water or working in the fields. After schools were introduced, they may also have been kidnapped on the way to class or when returning home. Normally the suitor would ask the Pim if there were any eligible females in the family. Then the suitor would coordinate with his brothers to follow the young woman and study her. The suitor and his family would then communicate to the girl’s family of their plans to kidnap her and on the day of the kidnapping they would often coordinate with the young women’s brothers to help. Wilfrida Atieno was kidnapped from Alego Central on her way to school in the 1970’s. She is still happily married to this day.

Role of Men and Women in Society

According to the folktale of Agola, women and men seem to play different roles in society. The woman is responsible for maintaining the homestead and for cooking and cleaning. Meanwhile, the man is responsible for farming and taking care of the livestock. Obong’o’s father is absent from the story, and the son seems to stay alone with his mother in the homestead. This could be because Obong’o’s mother was the second or the third wife in the family, or it could be because Obong’o’s father had died or was physically absent. Historically, ‘runaway fathers’ have been a major phenomenon within Siaya. During the 20th Century, it was common for the adult male to “rise one morning and disappear from the household and from Siaya” (Cohen, pg. 47). Between the 1940’s and 60’s, many runaway fathers migrated from Siaya to Southern Uganda to pursue job opportunities. It is possible that the absence of a father figure in the story of Agola reflects this historical phenomenon in Siaya. The original version of the folktale, however, must be dated before the emergence of formal schools in Siaya.

Witchcraft and Magic

In the folktale, Agola’s age mates betrayed her and practiced several forms of witchcraft in order to change her into inanimate objects and eventually into a dog. Within African Traditional Religion, witches are believed to be able to use incantations, rituals, or magic objects to poison, curse, or transform a victim (Mbiti, pg. 167). This folktale illustrates the traditional Luo belief in witchcraft. Witchcraft is still widely practiced in Alego today and is an object of fear. One person that I interviewed indicated that she has several aunts and grandmothers who are known practitioners of witchcraft in Alego.

Missiological Change

The Bible speaks to various cultural practices and beliefs that are similar to those described in this ethnographic study of Alego Central. The folktale of Agola upholds biblical principles such as the value, dignity, goodness, and beauty of human life. It also illustrates the sinfulness of jealousy and selfish competition. The folktale teaches a moral lesson to children that true beauty is more than skin deep, and that all people are worthy of respect and love. The dog with one eye represents a worthless and undesirable creature, but receives pity and affection from Obong’o. Furthermore, the folktale speaks to the importance of marriage and expresses the truth that “he who finds a wife finds what is good and receives favor from the LORD” (Proverbs 18:22). Despite attempts to curse and despise Agola, her life is not bound up in the hatred of others, rather there is a hidden Power a work to bring about good. I don’t have any major concerns with the rites of passage and the roles of men, women, and elders expressed in this folktale. Rather, the main element of this folktale and traditional beliefs in Alego that I feel needs missiological change relates to witchcraft. Witchcraft continues to have a strong grip in Alego Central and binds people in superstition, fear, and demonic practices.

The Bible recognizes the existence and authenticity of certain magical and supernatural powers (Exodus 7:11-22 and 2 Timothy 3:8). Nonetheless, from a biblical perspective, “magic and divination are two aspects of rebellion against God.” (Gehman, pg. 110). All witchcraft and sorcery are forbidden in the Bible because of their connection with demonic activities. “The Bible teaches that behind genuinely extraordinary, supernatural powers of traditional religion is the work of demonic spirits” (Gehman, pg 118). While the story of Agola is understood as folklore, it is important to confront the underlying attitudes and beliefs which are present in Alego regarding witchcraft. The Good News is that Jesus Christ offers freedom from the power, penalty, and presence of sin and that “perfect love drives out fear” (1 John 4:18).